Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed

The Holy Church, in her divine wisdom and inerrancy, placed the Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed, or All Souls, in the liturgical calendar on the day after the Solemnity of All Saints. This effectively unites the three states of the Church, the Mystical Body of Our Lord Jesus Christ, of which He is the Head. Yesterday, the Church Militant—formed by those on earth in a state of trial, fighting the good fight, to afterwards receive the crown of righteousness (cf. 2 Tm 4:7-8)—celebrated the Church Triumphant, praising and glorifying the Saints that are already in eternal beatitude. Today we turn our attention to our brothers who, although they number among the just, are still in Purgatory—the Church Suffering—fulfilling the temporal punishment due to their sins.

The triple dimension of sin

Almighty God can create nothing that is not for Himself. He gave us our being so that we might practice virtue, praise Him, reverence Him and serve Him above all things. Our obligation is no other, for it was not our parents who created our immortal soul, but God alone; and we are truly born of Him. When we sin, we misuse creatures, turning our back on God and offending Him. But, in His infinite goodness, the Saviour left us the Sacrament of Baptism to expunge original sin and all actual sins committed before receiving it, for those who already have the use of reason, as well as the Sacrament of Penance to absolve the faults incurred after Baptism.1 In being forgiven by Our Lord Jesus Christ Himself, by the lips of the priest, we avoid condemnation to hell. However, besides being an offence to God, sin also rises up against two other orders—that of the conscience and of the universe—and therefore, it is logical that it be put down and punished by these orders.2

The judgement of the conscience

We all have the Law of God written on our minds and hearts, as a criterion for discerning how foolish it is to follow sinful ways. Our conscience accuses us when we act wrongly, and points out the true path. For this reason, if someone in fact commits a sin, there is no room for doubt; rather, he is sure of his fall because he acted against his own conscience.

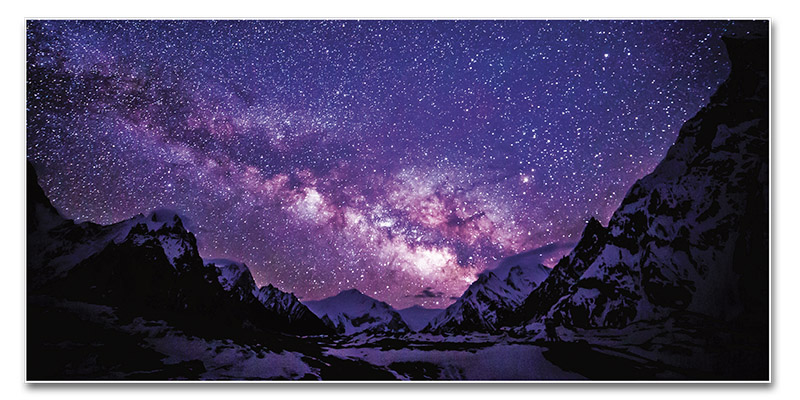

Sin wounds the perfect order of creation

God created the universe in perfect order; each planet follows its trajectory with precision—the earth does not collide with the sun, nor does the moon leave its orbit. Vegetable life also has its laws, by which plants continually seek sun and water, while animals, in turn, have regulated instincts. Man, however, is capable of proceeding in either order or disorder. When he follows the path of virtue, he acquires merit, which cannot happen with inferior beings, such as animals or plants. But if, conversely, he embarks on evil ways, he offends the order of the universe, as the Magisterium teaches: “Every sin in fact causes a perturbation in the universal order established by God in His ineffable wisdom and infinite charity, and the destruction of immense values with respect to the sinner himself and to the human community.”3

For this reason, when someone commits a serious sin, the order of the universe, shaken, is inclined to turn against the wrongdoer and obliterate him, unleashing the elements against him. Among the possible manifestations of nature against a sinner, we can imagine, for example, the earth opening up to swallow him, or fire falling from the heavens to devour him. We find mention of this in Scripture: “For creation, serving Thee Who hast made it, exerts itself to punish the unrighteous, and in kindness relaxes on behalf of those who trust in thee” (Wis 16:24). God, however, holds nature back from annihilating the culprit in the hope that he will do penance and attain salvation.

A debt remains after Confession

Nevertheless, we should bear in mind that Baptism forgives the double penalty due to sin—the one that is eternal, in consequence of the rejection of God, and the other, temporal, due to the inordinate attachment to creatures. While Confession absolves the first, it does not, on the other hand, always totally free us from the second, because the remission of this penalty depends on the intensity and perfection of the individual soul’s contrition.4 In most cases, a debt remains to be paid, either through penance performed in this life, or in the next, when the soul will undergo the rigours of Purgatory.

In what, then, does this debt consist, and how can the soul pay it? Let us imagine someone walking down the street on a rainy day who is suddenly covered from head to toe with mud after a car speeds by. Besides washing his face he knows that he needs to wash his clothes, especially if he is on his way to a wedding, where he cannot possibly appear stained with mud.

Similarly, when the soul separates from the body and appears at its particular judgement, it receives a special gift to enlighten its memory and conscience, bringing back a clear recollection of every detail of its moral and spiritual life.5 It then realizes that, having been forgiven in Confession for its offences against God and the eternal punishment due them, its face is clean. But the conscience cries out, because it feels dirty and in need of a “change of clothes”—that is, in need of paying the temporal punishment. Moreover, the soul may still harbour mentalities that are out of line with wisdom and good order, especially in today’s world, dominated by mechanization and technology. There may also be notions, whims or fixations that deviate from the perfect balance of holiness and are contrary, as a rule of life, to the principles of Faith. As long as the soul is affected in this way, it cannot stand before God and contemplate Him face to face, because these things impede it from understanding and loving Him, and relating with Him.

Why Purgatory exists

How can we obtain pardon for temporal punishment and adjust our outlook, in order to be ready to see God? During our earthly life we can achieve this by gaining the merits associated with good works—penances, prayers, works of mercy, and the like—or by indulgences which the Church grants, “making use of its power as minister of the Redemption of Christ, […] by an authoritative intervention dispenses to the faithful suitably disposed the treasury of satisfaction which Christ and the Saints won for the remission of temporal punishment.” 6

For those who have scorned these means, Purgatory becomes necessary, to “purify [the soul] from the consequences of sin”7 post mortem, and obtain remission of its punishment, as St. Thomas says,8 paying, for a time, the debt imposed by the offense to the conscience and to the order of the universe. “It is therefore necessary,” continues the teaching of the Church “for the full remission and—as it is called—reparation of sins, not only that friendship with God be re-established by a sincere conversion of the mind and amends made for the offense against His wisdom and goodness, but also that all the personal as well as social values and those of the universal order itself, which have been diminished or destroyed by sin, be fully restored.”9

Reformatory for our egoism

God, therefore, desiring that we enter His company free of stain, pure and perfect—for “nothing unclean shall enter it, nor any one who practices abomination or falsehood” (Rv 21:27)—created Purgatory as a type of reformatory, where our egoism is burned away in fire and we are re-educated according to the true view of all things and the love of virtue. After this period, our soul is sanctified and therefore it can be said that all who are in Heaven are saints.

This is also the reason why those who attain holiness here on earth do not go to Purgatory; or, in some instances, do so only long enough to make a genuflection, for example, as is said to have happened with St. Teresa of Avila. Or with St. Severinus, Archbishop of Cologne, who, despite his life having been consumed in fruitful apostolic works for the expansion of God’s Kingdom, was obliged to remain six months in Purgatory to expiate for a lack of recollection in praying his Breviary.10

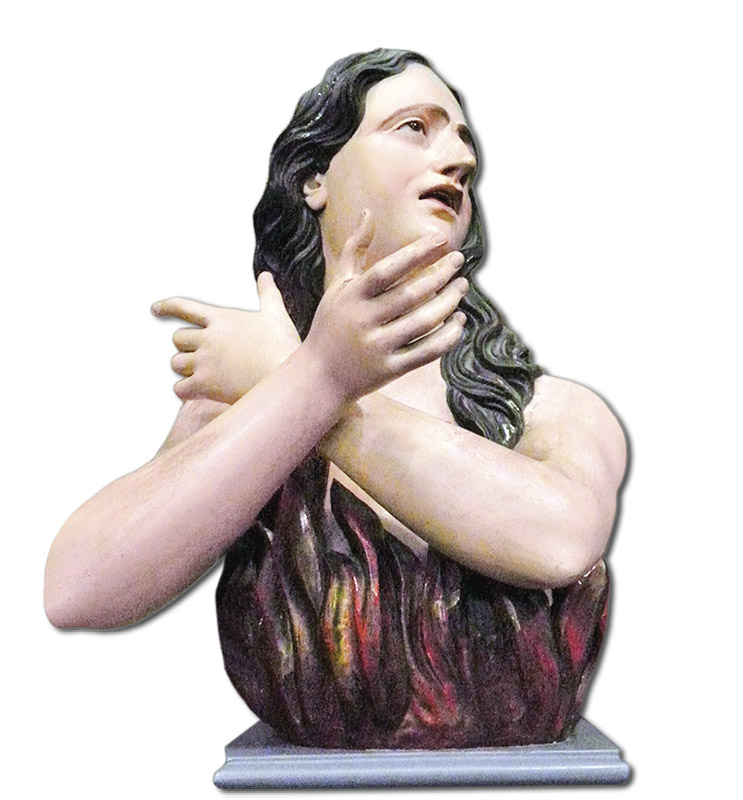

Hope amidst great torments

The souls in Purgatory suffer terribly, but with one great advantage over us: they enjoy the sure hope of Heaven. Hope is a virtue that causes joy and consolation, because it promises a future benefit. However, our hope during mortal life is doubtful and uncertain, because being here in passing, we may falter and commit a grave sin at any moment, with the risk of losing eternal life, if death follows immediately. In Purgatory, conversely, this hope is absolute, for it bears the certainty of having obtained its object; that is, of having won salvation.11

However, the torments there are dire, and while not equal to those of hell—since demons cannot torture the holy souls12 —they are fuelled by the same fire.13 To have a faint idea of the intensity of this heat, we may imagine a huge bonfire, and beside it, a painted representation of one. If we touch the painting, it will not burn us, but the moment we place our finger too close to the real fire we will experience excruciating pain. The difference between the painted and the real fire is similar to that between our earthly fire and the flames of Purgatory. According to St. Augustine: “that fire will be more violent than anything that man can suffer in this life,”14 and St. Thomas Aquinas adds: “the least pain in Purgatory surpasses the greatest suffering in this life.”15

Venerable Stanislaus Choscoca, a Polish Dominican, was at prayer one day when a soul from Purgatory appeared to him engulfed in flames. He asked him if that fire was more active and penetrating than earthly flames, and the soul exclaimed: “Compared with the fire of Purgatory, that of earth is like a light and refreshing breeze.” When Stanislaus courageously asked to feel it, the soul replied: “It is impossible for a mortal to bear such torments, but if you want a taste of it, stretch out your hand.” He did so, and the soul let a drop of searing sweat fall into his palm. Instantly, with a frightful shriek, the religious fell to the floor in a death-like swoon. After being revived by his confreres, who rushed to help him, he told them what had happened and recommended that the fact be published, to warn people of the terrible expiations of Purgatory. Finally, after a year, during which he felt continuous pain in his right hand, Brother Stanislaus died, urging his brothers to flee from sin in order to avoid the atrocious chastisements of the next life.16

The souls in Purgatory want to be purified

Notwithstanding these punishments, the souls in Purgatory are not chained there, trying to escape; rather, they fully accept their sufferings.17 Furthermore, if they knew of a thousand even more scorching Purgatories, they would want to cast themselves into them because what is most intolerable for them is to see themselves covered in stains that separate them from God. They yearn to be entirely pure and virginal to enter Heaven. This attitude evokes the ermine—the little white-coated animal that symbolizes chastity and innocence, preferring to die rather than soil its pure white coat.