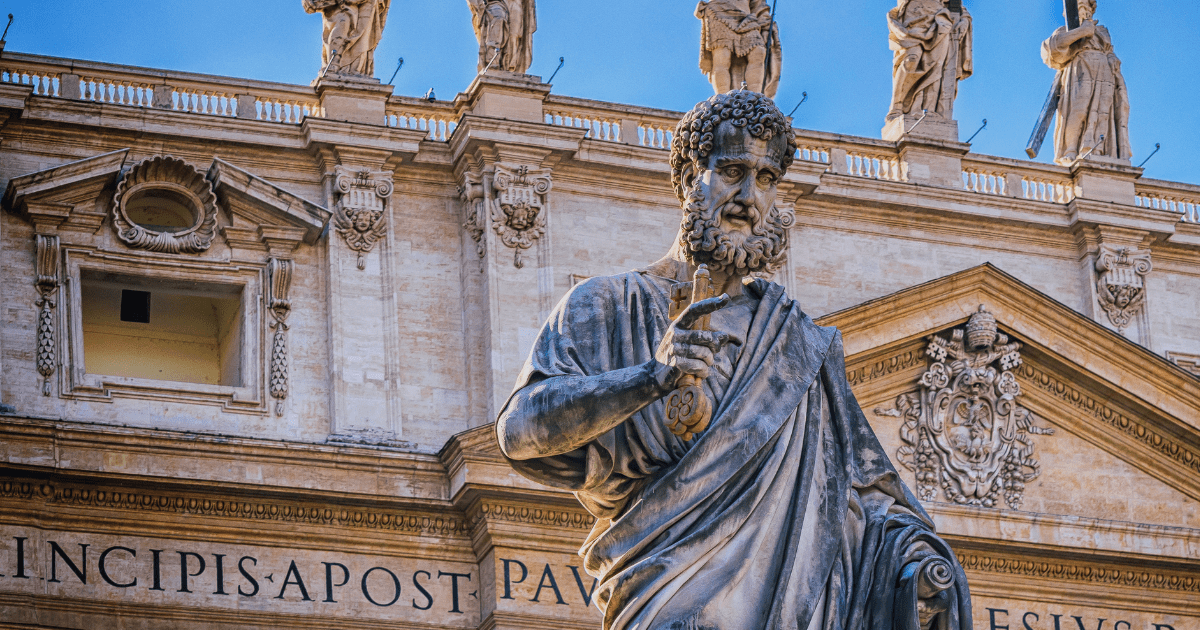

The Chair of Saint Peter

“And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (Mt 16:18).

In the last one hundred years, few passages of the Gospel have been the object of such vehement and passionate debate, for, as some allege, the present formulation deviates from the original written by Matthew—that the text was manipulated around the year 130 to justify the primacy of Peter and his successors over his brothers in the episcopate.

However, for centuries no one questioned the authenticity of this passage. It was not until the infiltration of rationalism into Biblical exegesis in the nineteenth century and the Protestant historicism of the twentieth century that attempts were made to disqualify it.

Biblical arguments in favour of the primacy of Peter

From the documentary perspective, the hypothesis of a supposed manipulation of this verse is unsustainable. The earliest texts that reproduce the passage in question reveal no trace of tampering: neither the Diatessaron (concordance of the four Gospels) of Tatian, from the middle of the second century, the writings of the Fathers of the Church previous to the fourth century, or the 4,000 presently known codices from the first eight centuries.

Rather, as can be seen in the box on page page 20, over 160 New Testament passages mention Peter occupying, in many of them, a position of preeminence in relation to the other Apostles. Even St. John, who speaks of the Prince of the Apostles in his Gospel to a lesser extent, due to the historical circumstances in which it was written—at the height of the debate with the Gnostics—offers two important references of the conferral of the Petrine Primacy: “You shall be called Cephas (which means Peter)” (Jn 1:42); and “Simon, son of John, do you love Me more than these? […] Feed my sheep” (Jn 21:15,17).

It is in Mt 16:18-19 that the doctrine regarding the Papacy is primarily founded; in the interpretation of these verses, the threefold metaphor used by Our Lord is usually emphasized: St. Peter is the foundation of the Church, because he is compared with the foundations that bind and give stability to every edifice; his power of jurisdiction is represented in the keys, which, in Biblical and secular language, symbolize dominion; and finally, the image of binding and loosing symbolizes the ability to create or abolish laws that bind in conscience.

Taken separately, the above interpretation could raise scepticism; but together with other New Testament passages, the writings of the Church Fathers and the praxis of the first centuries of Christianity it is a powerful argumentative tool. All of these proofs converge to affirm the indisputable primacy of St. Peter, given by Christ and uninterruptedly recognized throughout the history of the Church.

Testimony of the Apostolic Fathers

Of particular importance to the issue at hand is the history of the first centuries of the Church, which clashes head-on with the unwarranted supposition that the primacy of universal jurisdiction of the Roman Pontiff was an invention subsequent to the apostolic era.

Roman primacy is clearly shown in the letter by Pope St. Clement to the faithful of Corinth, regarding the rebellion in that community around the year 96. In the letter, the Pontiff does not apologize for interfering in the internal affairs of another Church—which would be normal, if he were simply primus inter pares, head of another sister Church—but he expresses regret for not having had the opportunity to intervene in the matter sooner. He warns those who do not obey his admonitions of the risk of committing grave sin, and expresses the conviction that his position is inspired by the Holy Spirit. It is noteworthy that the letter was received in Corinth without resistance and as a great honour, proven by the fact that even in the year 170, according to witnesses, it was read during the Sunday liturgy.

These facts are especially telling considering that the Apostle St. John, who, still alive, was in Ephesus, which was much closer to Corinth than to Rome. And it is nowhere recorded that either St. Clement, the faithful of Corinth, or St. John had any doubts concerning the authority of the Successor of Peter to settle the issue.

Another important testimony of this epoch in favour of the primacy of Peter’s Successor is the letter sent by St. Ignatius of Antioch (†107) to the Church of Rome. In it he also clearly shows—even more compellingly than in the previous example—the primacy of the Roman See over the others. Indeed, this missive differs substantially from those sent by him in the same circumstances (prisoner brought from Syria to Rome, where he was martyred) to other Churches, such as Ephesus, Magnesia, Tralles, Philadelphia and Smyrna. To these, he had written in a tone of authority; while in writing to Rome, the holy Bishop of Antioch uses a submissive tone.

Moreover, St. Ignatius acknowledges the power of the Church of Rome to lead the other Churches, teaching them as the disciples of the Lord; he entrusts his diocese in Syria to the pastoral care of the Roman See, and not to any other Church, even if it be closer.

A third testimony is that of St. Irenaeus of Lyons. Born between the years 130 and 140, he died around 202. He was a disciple of St. Polycarp, who, in turn, had been a disciple of St. John. Therefore, he was in almost direct contact with the apostolic age.

In his treatise Adversus hæreses, he speaks clearly and explicitly of the primacy of the Roman Church over all other Churches, referring to the aforementioned letter of St. Clement of Rome to the faithful of Corinth, which had among other objectives “to renew their Faith” and “declare the tradition that had been received from the Apostles.”

The intervention of Pope Victor I (189-199) concerning the date of the commemoration of Easter, which he decided to unify is also an expressive example. In the Province of Asia another calendar was followed. To resolve the matter, the Pope convoked a Synod of Italian Bishops in Rome, wrote to the Bishops of the entire world, and, finally, called on the Bishops of Asia to adopt the practice of the universal Church, of always celebrating Easter on Sunday. He declared that failure to comply would result in exclusion from the communion of the Church. Several bishops tried to moderate the papal decision, including St. Irenaeus, apparently to no avail. The fact is that gradually the Roman custom became common practice throughout Church, serving as a further example of the universal recognition of the primacy of the Pope.

The unexpected testimony of a heretic

However, arguments do not come only from the Catholic camp. Around the year 220, Tertullian, by then involved in the Monatanist Heresy, wrote a satire attacking Pope Calixtus I, who had published a decree to be read in all the churches diminishing the penitential discipline applied to adulterers and fornicators.

Sarcastically attributing the expression “Pontifex Maximus, namely, the Bishop of Bishops” to the Successor of Peter—titles then used by the Roman Emperor—the ill-fated ecclesiastical writer shows how all-encompassing the spiritual power of the Papacy was. Furthermore, his long tirade ends with a criticism of the claim of Calixtus I that his authority “to bind and to loose” was based upon that of St. Peter—thus providing valuable testimony to the long-standing awareness of the divine origin of the authority.

A noteworthy detail is that in attempting to refute the Pope, Tertullian—staunch opponent of the Church he once loved—without any objection cites the passage of St. Matthew’s Gospel contested by rationalists eighteen centuries later: yes, the Lord told Peter that he was the rock upon which He would build the Church; in fact, He gave him the keys, as well as the power to bind and loose, and entrusted the care of the Church to him. It is enough to read Tertullian’s word to see that he was referring to a fact peacefully accepted by all in that epoch, so close to the apostolic times; no suspicion could possibly be raised of any alteration of the Biblical text.

Supremacy founded upon a divine rock

St. Leo the Great—whose pontificate, from 440 to 461, was a significant turning point in the history of the Petrine Primacy—refers to the Church of Rome as magistra (master) and had no doubt about the authority of the Pope over the Council.

In the name of this authority he confirmed the doctrine defined by the Council of Chalcedon (451), initiating a practice that would be maintained by his successors and considered as necessary to confer validity to any ecumenical council. His famous Dogmatic Epistle was acclaimed with transports of enthusiasm by the Fathers gathered in Chalcedon, almost all of them Eastern, with the famous sentence: “Peter has spoken thus through Leo!”

St. Leo the Great developed the concept of Petrine sovereignty precisely from the previously cited verse of St. Matthew: “And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (Mt 16:18). He points out that this declaration of the Divine Master effectively applies to the Roman See and that the Pope, as Successor of Peter, has the very special mission of guiding and governing the universal Church, as well as the right to intervene and make decisions in the ecclesiastical issues of local Churches.

Unfortunately, historical data from the seventh century onward indicates a latent rejection by some leaders of the Eastern Church of the universal jurisdiction of the primacy of the Bishop of Rome, although still generally recognizing papal authority in doctrinal matters. Their growing resentment reached its sad outcome in the schism of 1054.

Complete and universal jurisdiction

Two important prerogatives stem from the primacy of Peter: the primacy of universal jurisdiction and papal infallibility.

The jurisdiction of the Pope applies fully and supremely to the universal Church, because it encompasses all authority granted by Our Lord to the Church. This jurisdiction is also monarchical, since Christ gave it to St. Peter and not the other Apostles, and unlimited, which means that the Pope is accountable to no one but God, for there is no recourse superior to him in the Church. Furthermore, it embraces the legislative, judicial and executive powers. It is also called an ordinary power in that it is constitutive of the very exercise of the Petrine ministry; immediate because it is exercised by its own right, without need for intermediaries; and Episcopal, since the objective of its exercise is eminently pastoral.

Consequently, the Pope is, on one hand, free to contact his Pastors and the faithful directly without coercion from civil power; on the other, he is the supreme judge of the faithful, to whom all have the right of recourse and no one, not even an ecumenical council, can contradict this.

Ordinary and extraordinary magisterium

Papal infallibility, for its part, is an inherent charism of the Petrine ministry which confers special assistance from the Holy Spirit to the Pope when he—speaking ex cathedra, that is, as supreme Pastor of the universal Church—defines a doctrine of Faith and morals.

Regarding papal infallibility, the Second Vatican Council clearly expressed, in the following terms, that the definitions of the Roman Pontiff “are justly styled irreformable, since they are pronounced with the assistance of the Holy Spirit, promised to him in blessed Peter, and therefore they need no approval of others, nor do they allow an appeal to any other judgment. For then the Roman Pontiff is not pronouncing judgment as a private person, but as the supreme teacher of the universal Church, in whom the charism of infallibility of the Church itself is individually present, he is expounding or defending a doctrine of Catholic faith.”

Together with this form of extraordinary Magisterium, the Pope also exercises an ordinary one, by orientation and teaching through encyclicals, constitutions, apostolic exhortations and speeches.

Infallibility does not mean impeccability

Finally, it should be remembered that neither the exercise of the Petrine ministry, nor the charism of infallibility bestow impeccability on the Roman Pontiff or, in other terms, confirmation in grace.

One of the rationalist arguments against the primacy of Peter is that the fisherman of Galilee was subject to sin, like all men. And, doubtless, he was. Nevertheless, his primacy does not rest upon human qualities, but in the almighty power of the Founder of the Church.

Christ did not call St. Peter because of his natural qualities; it was the grace of God that converted him into a solid and firm rock. “Simon, Simon, behold, Satan demanded to have you, that he might sift you like wheat, but I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail” (Lk 22:31-32).

In his recently published book-interview, Benedict XVI recalled that the duty exercised by the Roman Pontiff was not self-imposed. On the contrary, it is the Holy Spirit who chooses the Pope, using divine criteria: “You did not choose Me, but I chose you and appointed you that you should go and bear fruit and that your fruit should abide” (Jn 15:16).

The holiness of a Pope, therefore, is not inherent to the Petrine ministry, but comes from personal effort and, especially, from the action of grace. The possible infidelities in the life of any Roman Pontiff are always most grave, but do not abolish his authority, since God can make use of unfaithful instruments, and the Holy Spirit will prevent, with His assistance, personal sin from endangering the integrity of the Church, which was guaranteed by the promise of Our Lord Jesus Christ: “The gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (Mt 16:18).

In founding His Church, the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity wanted to establish a man capable of sinning but infallible in matters of Faith and morals as the supreme head. Unreservedly accepted by the consensus fidelium, it forms a happy union founded in charity and faith with the person and primacy of Peter.