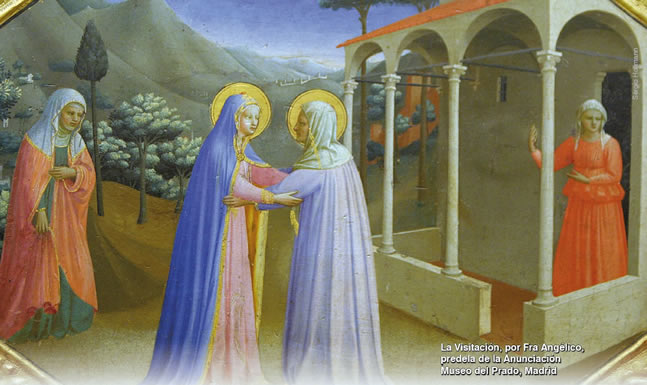

Intoned by Our Lady upon her encounter with St. Elizabeth, the Magnificat is a marvellous hymn inspired by the Most High, in which God sings His own glory through the lips of the most beloved of His children. It is also a beautiful, coherent, logical and serious message transmitted to the people of every age, by the virginal voice of Mary.

Exultation in God, her Saviour

The hymn begins with the word magnificat – from the Latin magnus, that is, great – to exalt Him who is Grandeur personified. It is thus acknowledged that God merits this superlative degree of praise and honour in His extrinsic glory, which is open to increase, for having wrought in Her, the Blessed Virgin, the fulfilment of the greatest and most auspicious divine promise made to humanity: the Incarnation of the Word.

Her soul hastens to pour out her feeling of profound gratitude, proclaiming how the Lord has thus revealed Himself as the Great One par excellence. And then comes the joy: “Et exsultavit spiritus meus in Deo salutari meo – my spirit rejoices in God my Saviour.”

To rejoice is to feel an intense jubilation, not just any contentment, like that which one might experience upon hearing that an investment had returned a little more than expected. This would be a small satisfaction

in comparison to that which is expressed by the word rejoice. Thus, Our Lady uses it to mean that her soul overflowed with joy in relation to God, her magnificent Saviour.

This happiness seems to become all the more intense, according to the thought completed in the following verse, as She considers her lowliness and notes how God saved Her in an extraordinary and super-excellent manner, not only making Her the Mother of the Word Incarnate, but assigning to Her the admirable role we see throughout the entire life of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

Legitimate joy for having been ennobled

Prado Museum, Madrid

After affirming her elation, the Blessed Virgin expresses the reason for this immense joy: “Quia respexit humilitatem ancillæ suæ – For He has looked with favour on His lowly servant.”

As a result of the attention that Our Lord has rendered Her, “ecce enim ex hoc beatam me dicent omnes generationes,” behold, “all generations,” namely, all people until the end of time, will praise Her, calling Her “blessed”.

“Quia fecit mihi magna qui potens est – the Almighty has done great things for me.” Once again, Mary’s joy at having been the object of a special design of the Omnipotent is evident: She, so humble, has become great through His power.

This passage contains an interesting teaching that merits consideration. As She rejoices in the divine grandeur, Our Lady also rejoices in having been ennobled by His condescension, and She knows that this magnitude of hers will make Her worthy of the praise and devotion of future generations. It is a unique glory that fills Her with happiness, and for which, filled with gratitude, She thanks God.

This attitude of Our Lady in accepting, reaping and loving Her own excellence, shows that it is legitimate for us to rejoice in the grandeur that God may bestow upon us. Provided that, like Mary, this joy is grounded in love for Him, realizing that such glory establishes a more intimate relationship between us and the Creator.

“Et sanctum nomen eius – And holy is His name.” That is to say, “God has done so with me, and He acted out of holiness.” This fabulous work that the Lord accomplished in His servant is marked by the infinite perfection with which He models everything that comes from His omnipotent hands.

Mercy for those who fear God

After thus manifesting the grandeur of God and Her own, Our Lady alludes to the aspect of goodness: “Et misericordia eius a progenie in progenies, timentibus eum – He has mercy on those who fear Him in every generation.”

The fact that God has done such a great thing with Her redounds as a benefit and a work of mercy for all those who will profit from it throughout the course of history. With one restriction, however: “timentibus eum –those who fear Him.”

This is another important lesson to be gleaned from the Magnificat. There are two fears: servile and reverential. Servile fear is that which a slave has, for example, in doing the will of his master for the dread of suffering harsh punishments if he does not obey. Reverential fear is that which is shown to another, not out of apprehension for the punishments that may be inflicted, but out of respect and veneration for this person’s superiority and our unwillingness to give any offence, or transgress the obedience that is rightfully due.

We find a marvellous example of reverential fear in the ardent words St. Teresa of Jesus addressed to Our Lord: “Even if there were no Heaven, I would love Thee; even if there were no hell, I would fear Thee.” In other words, even if God did not cast into Gehenna those who revolted against Him, for being who He is who He is and due to the infinite qualities by which He surpasses us, we would fear not to do His will. This is the highest and noblest form of reverential fear.

Accordingly, to those who love God with such a love as to even fear Him – not only on account of hell, but above all for not wanting to displease Him in His infinite sanctity –, to them is opened the inexhaustible mercy of God: “Et misericordia eius a progenie in progenies, timentibus eum.”

It is important to highlight that frequently divine goodness is not bound by this restriction, but surpasses itself in extremes of solicitude towards even those how have little or no fear of God, before their being touched by grace and converted.

For example, we can suppose that St. Paul did not have fear of God on the way to Damascus. But, struck by a lightning bolt, he fell from his horse, lost his sight and heard Our Lord’s voice questioning him. When he arose, he was another man, becoming the great Apostle of the Gentiles. An extraordinary action of divine mercy – most likely owing to the supplications of Mary – enveloped a soul that until then did not fear God.

The fall of the proud and the lifting up of the humble

“Fecit potentiam in brachio suo, dispersit superbos mente cordis suis – He has shown the strength of His arm, He has scattered the proud in their conceit”.

Let us understand what “has shown the strength of His arm” means. It is a metaphor, for God, a pure spirit, has no arm. For a man, however, the arm is a member by which he shows his strength and carries out the decrees of his intelligence and his will. Thus, in referring to the “arm of God,” Our Lady helps us to see that He takes forceful measures against the haughty and proud, those who close themselves to the action of grace and neither fear nor love Him in their hearts. To Through the Incarnation, God broke the power by which the devil and his followers tormented the good May 2019 · Heralds of the Gospel 25 these, God shows the power of His arm.

The thought is completed in the following verse: “Deposuit potentes de sede, et exaltavit humiles – He has cast down the mighty from their thrones, and has lifted up the lowly.”

Through the Incarnation of the Word, God broke the power by which the devil and his worldly followers tormented the good. Thus, he deposed them from their thrones, and lifted up those that were persecuted.

by Bernardino Mariotto – Museu Cívico

de Morrovalle (Italy)

Someone might object that in the judgement of Our Lord, the opposite happened, since Annas, Caiaphas, Pilate and their ilk were on their thrones when they persecuted and killed Him.

It is true. But this story is not told in its entirety. For what took place after Jesus died was exactly what those powerful men had wished to avoid. He resurrected, triumphed over death and over all of His tormentors. With Him triumphed the Holy Church, the Apostles and Our Lady, the humble who until then were despised. And they will be glorified and exalted forever, whereas Annas, Caiaphas and Pilate will be spoken of with opprobrium and horror. Thus is confirmed the veracity of the statement: “Deposuit potentes de sedes, et exaltavit humiles.”

This idea still prevails in the continuation of the canticle: “Esurientes implevit bonis, et divites dimisit inanes – He has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich He has sent away empty.”

Our Lady does not intend to allude to material or financial resources here. She refers, above all, to those who lack spiritual goods, to those who lack spiritual goods, to those poor in heavenly gifts. Out of the infinite abundance of His mercy, God heeds the poor in spirit who humbly beseech these graces. On the other hand, He sends away the “rich” empty handed, those who, in their pride, see themselves as entirely satisfied; that is, He does not make them participants in the treasure of His supernatural gifts.

The promise made to Abraham is fulfilled in Mary

Finally, Our Lady returns to the central point that inspires this wonderful hymn: “Suscepit Israel puerum suum, recordatus misericordiæ suæ – He has come to the help of His servant Israel, for He has remembered His promise of mercy.”

That is to say, the Chosen People will soon receive the Messiah promised for millennia, whom God will send into the world, recalling that His mercy has thus pledged it. From which flows the conclusion: “Sicut locutus est ad patres nostros, Abraham et semini eius in sæcula – the promise He made to our fathers, to Abraham and to his children for ever.”

The promise made to Abraham, founder of the Hebrew race, and to his descendants over the course of centuries, that the Saviour would be born from his lineage, has been fulfilled. Our Lady carries in her womb the Expectation of Nations. She, a daughter of Abraham, will give birth to the Son of God.

And thus the Magnificat, this inestimable jewel, this marvellous canticle of wisdom, humility and grandeur, harmoniously closes by reflecting on the Incarnation of the Word, just as it opens in the first stanza.