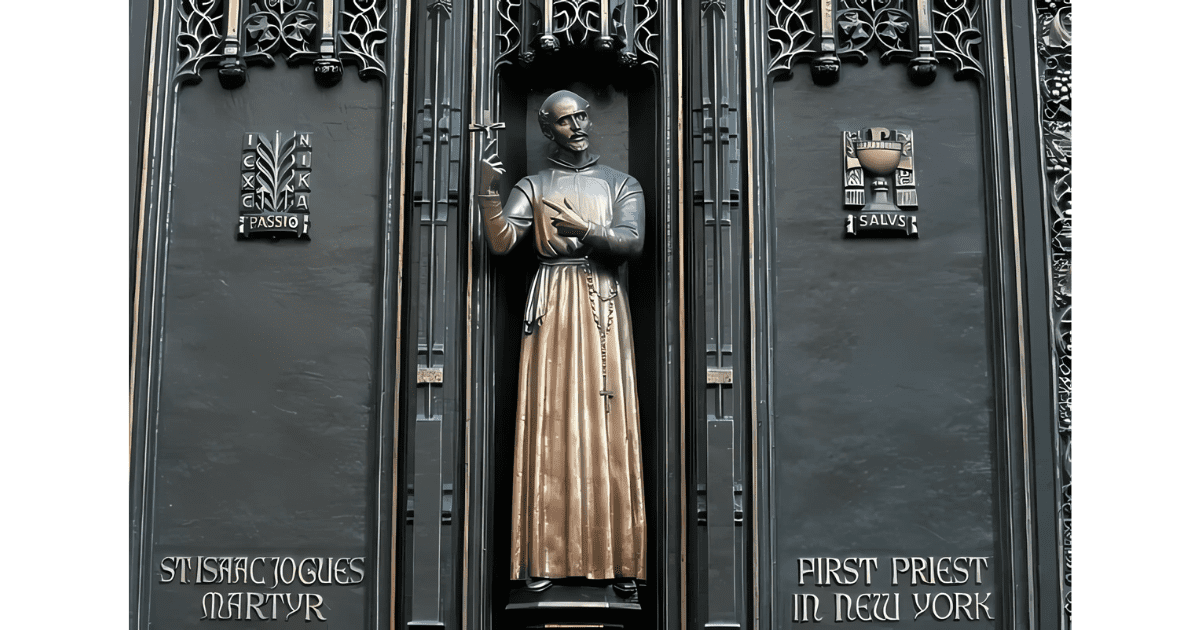

Saint Isaac Jogues – A Sacrifice of Pleasing Aroma to the Lamb Once Slain

From the deck of the galley came cries of panic, interspersed with claps of thunder:

— The ship is sinking! We are lost!

Fr. Jogues, who was on his knees in his little cabin reading the Book of Isaiah, heard the terrified shouts. He immediately consecrated the vessel to God, along with its crew and passengers. Then he went forth to face a scene of despair and confusion.

With great effort, he imposed silence and made everyone listen to him. Compelled by that imposing figure, who stood among them like an apparition, the travellers momentarily forgot their fears. With a calm and steady voice, the priest repeated to them the words of Isaiah that he had been reading, bidding them to ask forgiveness for their sins. After this brief preparation, he gave them sacramental absolution. Only then did everyone notice that “the stridor of the wind was died down. The storm was past. They were saved.”1 The ship quietly continued on its course.

Struck with wonder, many on board associated the sudden quelling of the storm with the presence of that minister of God, and asked themselves, like the Apostles aboard the boat: “Who then is this, that even the wind and sea obey?” (Mk 4:41). Others gratefully acknowledged the even greater miracle, which, through those consecrated hands, had been wrought in their repentant souls, cleansing them of the stain of sin.

Let us make the acquaintance, even if in general strokes, of the missionary adventure of St. Isaac Jogues, a son of St. Ignatius of Loyola who crossed the Atlantic Ocean twice in his zeal to give his life for the evangelization of North America.

The forging of a missionary

It was in the historic city of Orleans, marked by the heroism of St. Joan of Arc, that Isaac Jogues was born in 1607. From the outset of his religious and intellectual formation, he felt the desire to become a missionary and to evangelize distant lands. Having entered the novitiate in Rouen, he dreamed of the missions in Ethiopia or in Japan. However, his master of novices, Fr. Louis Lallemant, portended: “You will die in no other place but Canada.”2

There in Rouen, he took his vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, in the perpetual service of God within the Company of Jesus, and shortly afterwards, he was sent to study Philosophy at La Flèche College in Anjou, the most illustrious Jesuit educational establishment. After completing the years of the course, he was called back to the College of Rouen, where he started to lecture. There he met some Jesuits recently arrived from Canada. Among them were Fathers Gabriel Lalemant, Jean de Brébeuf and Énemond Massé, who related the adventures and the risks they confronted in the New World. Captivated by the prospect of such an ample field of apostolate, he also yearned to conquer souls for Christ in those distant and uncultured territories.

The North American Mission was considered, at that time, one of the most difficult, due to the harsh climate, poor lodging, the long distances to be covered, and above all because of the ferocity of the native populations which included the Hurons, Iroquois, Mohawks and Algonquians.

While the Hurons had not entirely abandoned their nomadic lifestyle, they had already begun to cultivate the soil and take the first steps toward a settled way of life – an indispensable condition for the fruitfulness of any apostolate. While they and the Algonquians were allied with the French, the Iroquois received arms and instructions from the Dutch and the English who fomented rivalries between the tribes, much to the detriment of the evangelization.

The beginning of an epic

Ordained a priest in 1636, before the completion of the complementary studies of his spiritual formation at Clermont College, in Paris, Jogues set sail for Canada, dropping anchor there in July of the same year. He wrote to his mother of his arrival at the missionary village of Saint-Marie with these words: “I do not know what it is to enter Heaven, but this I know – that it would be difficult to experience greater joy than I felt in setting foot in the New World, and celebrating Mass in Quebec on the Feast of the Visitation.”3

His contentment grew when he was assigned to the apostolate in Ossossané, the Huron region, in Trois-Rivières. The voyage was arduous and hazardous, for the only means of transport were the canoes of the natives who had come to trade their furs in the city, and if they became vexed, they were known to simply abandon their passenger in the wilderness or throw him into the St. Lawrence River.

After a relatively tranquil voyage of eighteen days, Fr. Isaac was given a warm, fraternal welcome by Fr. Brébeuf who had been eagerly awaiting him. Then he began his activities, dividing his time between the study of the indigenous language, care of the sick and catechesis.

After only five days, as he was making the rounds to the villages of the region, he was beset by extreme physical malaise. Forty-eight hours later, he had a high fever. He had caught smallpox, the epidemic that spread rapidly and laid low missionaries and natives alike, due to the primitive hygiene conditions.

The natives were quick to blame the disease on the “Blackrobes” as the priests were called – an allusion to the Jesuit cassock. They alleged that their “magic words” brought death and “the baptismal water that they poured over the heads of children in danger of death was the venom that really killed them.”4

The months passed and the number of casualties in the villages mounted. Even in the missionary community, the religious fell ill, one after another. This is one of several epidemics that “in a few years reduced a population of thirty thousand to twelve thousand habitants.”5

The Jesuits decided to make a novena of Masses with the intention of ending the defamatory campaign that had been unleashed against them. On the ninth day, calm was restored in a way that filled everyone with wonder. At the end of 1637, the preaching started to meet with a warm reception and was even well spoken of, both in Ossossané, where Fr. Jean de Brébeuf lived, as well as in the Mission of St. Joseph, in Ihonatiria, where Fr. Jogues had gone.

Preparation for martyrdom

Evangelizing fruits, however, were scarce. In one of Fr. Jogues’ missions, one hundred catechumens were baptized, but all had been in grave risk of death. Only in 1637, six years after the arrival of the Jesuits in Canada, did Fr. Brébeuf baptize the first healthy adult.

Even when they saw their zealous apostolate go uncrowned by immediate fruit, the missionaries remained willing to irrigate those lands with their own blood. Charity had spurred them to abandon their country, to undertake perilous journeys and confront monumental difficulties to save souls, and they would take this love to its summit, through martyrdom.

St. Thomas Aquinas teaches that “martyrdom is the most perfect of human acts in respect of its genus, as being the sign of the greatest charity, according to John 15:13, ‘Greater love than this no man hath, that a man lay down his life for his friends.’”6 Since it is such a sublime and munificent act, it not was by a sudden urge that our Saint desired it. Longings to unite himself to the sufferings of Christ inundated his soul, and, just like Fr. Brébeuf, he made the formal offering his life: “Fr. Isaac Jogues, supplicated: ‘Lord, give me to drink abundantly of the chalice of Thy Passion.’ An interior voice enlightened him that his entreaty had been heard.”7

Without manifesting itself outwardly, grace had been preparing his soul for this lofty oblation, as one of his biographers narrates: “He was reluctant, however, to reveal any of the virtues that he practised and was prevailed upon to speak of the graces God had given him only at the insistent demands of Buteux. He was forced by his friend to put down in writing the visions with which God had encouraged him at certain crises in his life. Other Divine interventions, Buteux himself recorded. Thus, Buteux learned that after the vision at Sainte-Marie wherein Father Jogues was told Exaudita est oratio tua; fiet tibi sicut a me petisti; confortare et esto robustus [Thy supplication has been heard; may it be done as thou has requested of Me; be strong and courageous], Isaac offered himself up a hundred times a day as a victim extraordinary to God.”8

The offering is accepted

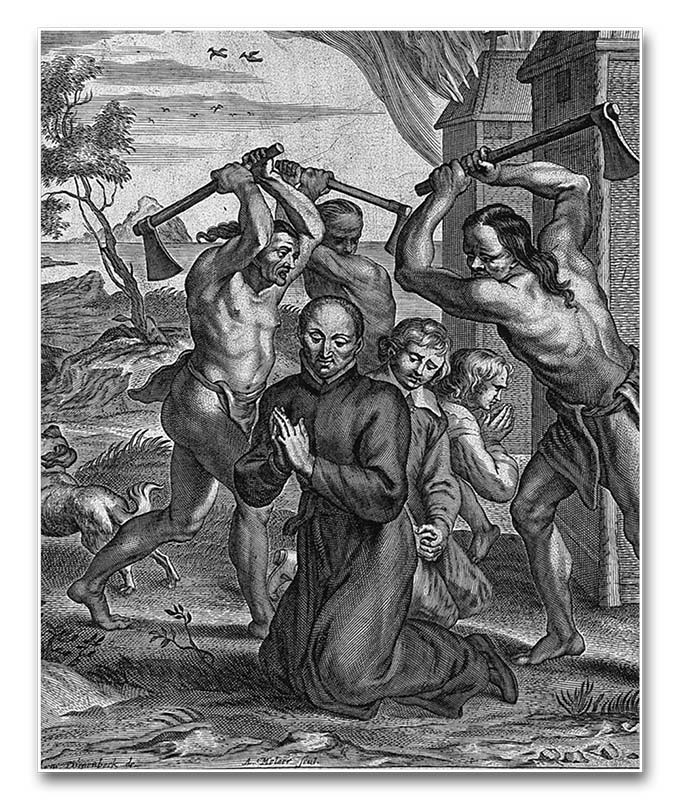

The offering of the missionary seemed about to be consummated when, in August of 1642, he was captured by the Iroquois as he travelled down the St. Lawrence toward Quebec. On the way to captivity, his confrere, Br. René Goupil, in the midst of torture, requested of him the privilege of pronouncing the religious vows, which he had not yet made due to ill health. “And so, in the name of the Father Provincial of France, Father Jogues gave René permission to pronounce the vows of the Temporal Coadjutor in the Society of Jesus.”9

Suffering and torment reached new levels when they arrived at the village of Ossernenon, in present-day New York. Fuelled by hatred, “the Iroquois mercilessly lashed Fr. Jogues with sticks and iron rods; they tore out his beard and his fingernails, they crushed his fingertips, and hacked off his right thumb; the children diverted themselves by applying coals and blazing irons to his skin. Finally they hanged him between two posts with tight cords tied to his wrists.”10 One of the savages, seeing that there were still “two entire nails on one of Fr. Jogues’ hands, pulled them off with his teeth.”11 During the night they left him lying naked on the ground, covered with wounds, and harassed by swarms of insects.

René Goupil was killed a few weeks later by a tomahawk blow. Fr. Jogues, however, remained a slave of the Iroquois for a further thirteen months of cruel captivity, during which he suffered as much in soul as in body, for he was continually assailed by trials and temptations. Considering himself to be chastised by God, he feared that he would be eternally condemned if those torments would not soon come to an end.

How could he have become overwhelmed in such a trial, when he was on the brink of receiving the long-desired grace? This is something that only happens with those who offer themselves as victims, and who, just when the oblation is about to be consummated, fail to associate their sufferings with the offering they made and believe themselves to be dying through their own fault. God permits this to increase their merits, and consequently, their glory in Heaven.

A prophetic vision

About two weeks after the death of Brother René, Fr. Jogues had a vision in his sleep. He was returning to the village of Sainte-Marie and found, instead of the habitations surrounded by a rustic palisade, what seemed to be a city venerable with age, surrounded by thick walls, and guarded by towers of amazing beauty. Awestruck, he doubted that it was his village. Some Indian acquaintances came out and assured him that it was indeed the same village. And so as he passed through the first gate, he soon came upon a second, upon which he saw the picture of a slain lamb and above it two letters, “L. N.”, which signified “Laudent Nomen eius – Praise to His Name.”

He wanted to keep going, but a soldier blocked his passage, telling him that he would be taken to the judge and leader who would punish him for his temerity. Despite the fact that he had duly halted, he was led to a beautiful chamber, similar to a chapter room where there was an old man, majestic and venerable, like the Ancient of Days of Scripture (cf. Dn 7:9,13,22). The latter, heard the accusations made by the soldier against Fr. Jogues, and without asking the accused anything, he lashed him three times. Feeling a pain as intense as the blows received from the ferocious Indians, the holy missionary suffered with full resignation, even though he did not understand what was happening.

“Finally,” he recounts, “my Judge, almost as if he were in admiration of my patience, laid aside the rod with which he had been striking me; he clasped his arms about my neck most sweetly, and soothed my grief, and imparted to me a feeling of happiness wholly divine and entirely inexplicable.”12

The strength and the consolation that he drew from this vision mitigated all his exertions and crosses.

Respite before the final struggle

Freed from captivity, thanks to the intervention of some of the Dutch, Fr. Jogues returned to France to recuperate from this first near-martyrdom, even though he had wanted to remain at the mission to continue baptizing, converting and suffering.

When he arrived in Rennes, he was unrecognizable! He was so altered that the Jesuit rector who knew him before his departure for Canada, asked him:

— Do you know Fr. Jogues in New France?

— I know him very well, reverend Father.

— And do you have news of him? Is he still alive, or as some say, has he been burned by the Iroquois?

— No, my father, he is alive. For it is he who stands before you and asks for your blessing

Because of his mutilated fingers, the heroic missionary was canonically impeded from celebrating Holy Mass. Accordingly, he wrote a letter to Pope Urban VIII, explaining his situation in detail, and appealing for authorization to offer the Holy Sacrifice despite his deficiency.

With lively interest, the Supreme Pontiff requested more information about Fr. Isaac Jogues, his mission in the New World and everything that he had suffered in captivity among the Iroquois. Deeply moved by the narrative, the Holy Father exclaimed: “It would be shameful, that a martyr of Christ be not allowed to drink the Blood of Christ!”13 And, straightway, he granted the petition. Upon climbing the altar steps, after a interlude of twenty months, “It seemed to him like his first Mass over again.”14

the martyrdom of Fr. Isaac Jogues

The holocaust is consummated

He spent a short period in France to recover from his torments. His most ardent desire, however, was to return to the front to continue his mission of saving souls, and especially, of suffering. It was on his return trip to Canada, in 1644, that the storm at sea, narrated at the beginning, occurred. From this time onward, Fr. Jogues was widely considered a true man of God.

In September 1646, after two years of mission in Montreal, he was commissioned to negotiate a peace treaty with the Iroquois. Despite his natural repugnance to return to the place where he had been so grievously tortured, his only ambition was to do whatever God asked of him and he would rather die a thousand deaths than refuse.

Some weeks later, acting on the transitory peace that had been obtained, Fr. Jogues was chosen, along with Br. Jean de Lalande, to go and attempt to evangelize the Iroquois. Upon receiving the order from the superior, he jubilantly exclaimed, “I shall be happy if the Lord will complete the sacrifice, where He has begun it!”15

On October 17, of 1646, as he set foot once again in Ossernenon, Fr. Isaac Jogues was captured and cruelly tortured. The next day, an Indian killed him with a hatchet blow, and then decapitated him. It was thus that he consummated his holocaust, as a sacrifice of pleasing aroma to the Lamb once slain. And it was this sacrifice, which, united to those of his other Jesuit brothers also martyred in those wild lands, would reveal its fruitfulness, in future centuries, with the flowering of the Catholic Church on North American soil. ◊