St. Teresa of Jesus – A Great Lady, a Great Nun, a Great Saint

At dawn a beautiful spectacle can be viewed from the Cantareira mountain range, a few kilometres from the city of São Paulo. As darkness gives way to diaphanous blue, the swiftly moving clouds take on a fiery tone. Successively, the red turns to gold and, on the horizon, slowly and majestically, the sun rises, painting the landscape with vivid hues. Before the spectacular panorama, the observer becomes awestruck, and is almost instinctively prompted to think of the magnificence of its Author.

If material splendour is capable of evoking the Creator what of a soul divinized by grace and worth more than the natural good of the entire universe? There are people so united to God that they, so to say, personify grandeur; they shine with the light of the divine life that is in them to a high degree.

One such soul stood out in the sixteenth century. “She had a vast and privileged intelligence, at once strong and nuanced, made for high flights. Moreover, [she was] gifted with a resolute will and an entirely dominated sensibility. […] Ultimately, she was one of the most privileged exemplars in the order of nature of the greatness of the human personality, shining with sublime flights of grace, embodying the concept of the perfect human type for a religious matriarch.”

She fulfilled God’s plans for her with such perfection and fidelity that greatness was incorporated into her name. In her native Spanish, St. Teresa is known as el Grande (the Great).

Sickness and an invitation to contemplation

She was born Teresa de Cepeda y Ahumada on March 28, 1515, in Gotarrendura in the province of Avila, into a large family of lower Spanish nobility. As a child, she was captivated with the stories of saints, and when she heard of the feats of the first martyrs, she saw this as the most direct path to Heaven. She decided, then, to run away with her little brother Rodrigo to the land of the Moors, where they could surrender their lives in defence of the Faith. They were already far outside the city walls when an uncle found them and brought them home.

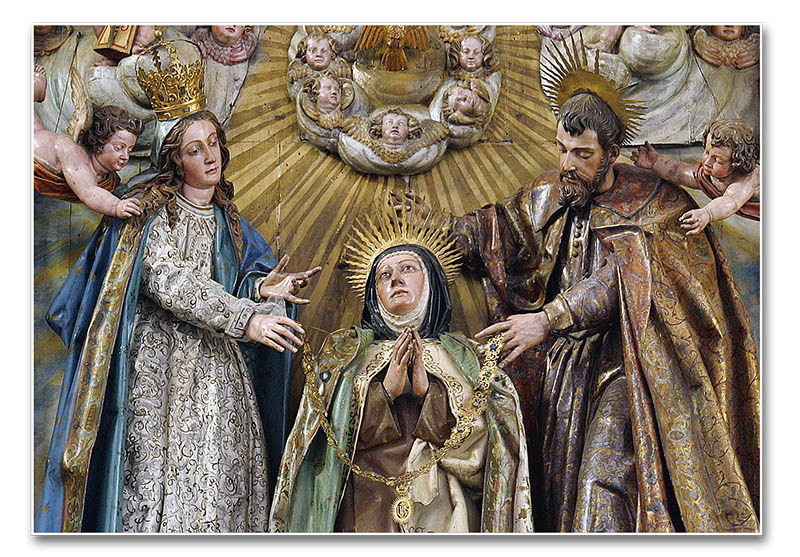

Having lost her mother at age fourteen, Teresa placed herself in Our Lady’s hands as her only Mother. At twenty, she entered the Carmelite Monastery of the Incarnation in Avila—initially against her father’s will—where she pronounced vows a year later.

Almost 200 religious lived there under the mitigated rule of Mount Carmel. Sister Teresa was given a spacious cell, along with the freedom to attend visitors at any hour and to go to the city for any reason. The nuns would spend hours speaking in the parlour which had been converted into a type of social centre.

However, the Cross, an essential element of greatness, did not delay long in coming to this chosen soul. Shortly after her religious profession, her health declined to such a degree that her father, Alonso de Cepeda, obtained permission to take her to the village of Becedas, to a lady whose medical treatments were renowned for their efficacy. During the trip, Teresa learned of mental prayer through the book Third Spiritual Alphabet, by Fr. Francisco de Osuna, and felt called to a life of contemplation.

Meanwhile, her treatments did not produce the desired result; “At the end of two months, the severity of the remedies had almost ended my life.” Upon returning to her father’s house, an intense muscular contraction left her unconscious for almost four days. They would have buried her, had her father not objected. She awoke in a lamentable state: “I was all doubled up, like a ball, and no more able to move arm, foot, hand or head than if I had been dead.”

Even in this condition, Teresa wanted to immediately return to the convent. Her soul, like Job’s (cf. 2:10), was admirably steeled: “I was quite resigned to the will of God, even if He had left me in this condition for ever. My great yearning, I think, was to get well so that I might be alone when I prayed, as I had been taught to be.”

After three years of paralysis, her prayers obtained a cure, from St. Joseph, and from then on devotion to the Holy Patriarch took first place in her life.

of St. Joseph, Avila

Interior struggle and peace of soul

With compromised health, Teresa resumed community life in the Monastery of the Incarnation. Nevertheless, there she grew lax, neglecting the interior prayer in which she had made such progress during her illness. The monastery had lost the original fervour of the vocation and had drifted from the Carmelite spirit. The parlour, which was open to society ladies, flowed with frivolous and worldly banter negatively influencing the saint’s spiritual life.

After a time, advised by Friar Vincent Varrón, a Dominican priest, she resumed the practice of mental prayer, although this cost her at first: “It is a fact that, either through the intolerable power of the devil’s assaults or because of my own bad habits, I did not at once betake myself to prayer; and whenever I entered the oratory I used to feel so depressed that I had to summon up all my courage to make myself pray at all. People say that I have a little courage, and it is clear that God has given me much more than to most women, only I have made bad use of it. In the end, the Lord would come to my help.”

One day, while praying in her oratory, reflecting that her vain conversations had increased the sufferings of Christ, she felt piercing sorrow for her faults. She cast herself at the foot of an image of Our Lord wounded, promising not to leave there until He had strengthened her so as not to offend Him again. “Porfié y valióme — I insisted and He helped me,” she would later say, narrating the episode.

“My soul”—she recounts in The Life of Teresa of Jesus, her autobiography,—“gained great strength from the Divine Majesty: He must have heard my cries and had compassion on all my tears. I began to long to spend more time with Him.” And she adds, “When picturing Christ in the way I have mentioned […], I used unexpectedly to experience a consciousness of the presence of God, of such a kind that I could not possibly doubt that He was within me or that I was wholly engulfed in Him.”

God makes her enter the crucible of trial

The holy Carmelite was growing in intimacy with God through this practice of prayer, when temptations began to appear. The Most High wanted her to enter the crucible of trial. However, just as turbulent ocean waves prove the strength of the rocks that they strike at the shore, the waves of trial, when confronted with confidence and dignity, make great souls even greater.

“As there have been cases recently in which women have been subjected by the devil to serious illusions and deceptions, I began to be afraid, for the delight and the sweetness which I felt were so great and often I could not help feeling them.” She was referred, then, to Fr. Gaspar Daza—who would later be of great help and support to her in the Carmelite reform—as the man who could help her to discern the origin of this joy. He was a renowned theologian, “a pattern to the whole place and a person whom God keeps there for the help and profit of many.” She became acquainted with him through Francisco Salcedo, a holy and virtuous noble and a distant relative.

The theologian examined her case and sent her the reply that her experiences that she claimed to have of God in mental prayer were sheer imagination and the work of the devil. Furthermore, the fame of the Carmelite nun had spread throughout the city, and before long many opined that the beata from the Incarnation Monastery was possessed by devil. Teresa kept in the depth of her soul “a very deep inward assurance that this was of God, especially when I was engaged in prayer,” because on these occasions she always felt “better… and developed greater fortitude.” However, her heart was distressed: “Certainly this is a grievous trial to experience and one needs to be careful—women especially so, since we are weak, and may come to great harm if we are told in so many words that we are being deluded by the devil.”

Counselled by Father Daza, she sought assistance from the Jesuits, whom she took as confessors, since they understood well the language of the spiritual way that Providence had mapped out for her. The counsels of St. Francis Borgia and, later, the Franciscan St. Peter of Alcantara, encouraged her during this crucial period.

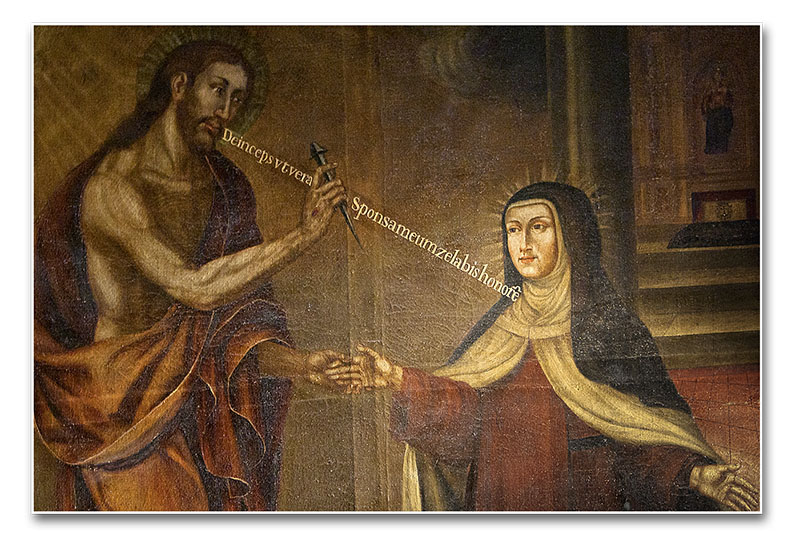

Christ seemed to walk always at her side

“I will have thee converse now, not with men, but with angels.” These were the words that Teresa heard in the first ecstasy granted to her by divine grace. “Since that day I have been courageous enough to give up everything for the sake of God, Who in that moment—for I think it happened in no more than a moment—was pleased to make His servant another person.” Along with the trials, Christ continued to speak to her frequently and seemed to walk always at her side: “Whenever I became slightly recollected or was not greatly distracted, I could not but be aware of His nearness to me.”

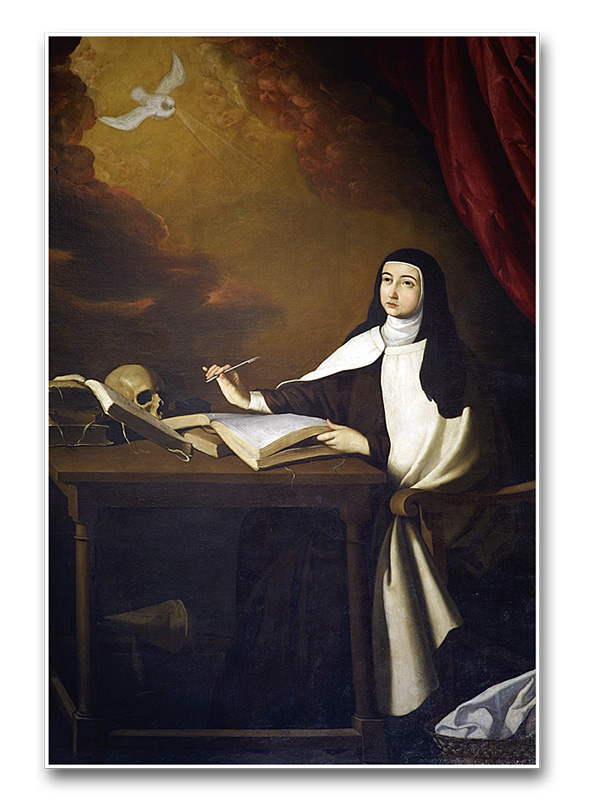

Often during these intimate moments with Jesus, she felt the fire of divine love in her soul. More than once her heart was pierced by an Angel, leaving physical marks of transverberation: “It pleased the Lord that I should sometimes see the following vision. I would see beside me, on my left hand, an Angel in bodily form […]. In his hands I saw a long golden spear and at the end of the iron tip I seemed to see a point of fire. With this he seemed to pierce my heart several times so that it penetrated to my entrails. When he drew it out, I thought he was drawing them out with it and he left me completely afire with a great love of God. The pain was so sharp that it made me utter several moans; and so excessive was the sweetness caused me by this intense pain that one can never wish to lose it, nor will one’s soul be content with anything less than God.”

No time to speak with God of trivialities…

After a vision of hell, around the year 1560, God’s great mission for her was revealed in her soul. Learning of the dreadful torments of the reprobates, she felt immense pity in seeing the great number of souls that condemn themselves. The state of the Church deeply afflicted her, for she heard of the harm caused at that time by the sects that had begun to spread throughout Europe. She saw with grief the crowds that turned from God and how few were His friends.

She then began asking herself how she could be of use to the Church at this terrible crossroads: “it occurred to me that the first thing was to follow the vocation for a religious life which His Majesty had given me by keeping the Rule with the greatest possible perfection.” And she counselled her sisters in the vocation: “busying ourselves in prayer for those who are defenders of the Church, and for the preachers and learned men who defend her, should do everything we could to aid this Lord of mine Who is so much oppressed by those to whom He has shown so much good.”

Beginning with this resolution, her life was marked by a growing love for her Religious Order, thinking not of spiritual gain, but of serving the Mystical Body of Christ, for whose cause her heart was consumed with zeal. “Behold my desires, my God, and the tears with which I beg this of Thee […] Have pity upon all these souls who are being lost, and help Thy Church. Do not permit more harm to be wrought to Christendom, Lord.”

She saw, above all, the need to reform Carmel and felt the call of Providence to fulfil this mission. She desired communities that were not just refuges for contemplative souls, concerned with nurturing and enjoying company with God, but for souls who were torches of love occupied with making reparation for the evil done to the Church. “The world is on fire. Men try to condemn Christ once again, as it were, for they bring a thousand false witnesses against Him. They would raze His Church to the ground […] No, my sisters, this is no time to treat with God for things of little importance.”

Founding of St. Joseph and beginning of the Carmelite Reform

This desire to found religious houses of strict observance to the original Carmelite Rule was soon confirmed and encouraged by Our Lord. “One day, after Communion, the Lord gave me the most explicit commands to work for this aim with all my might and made me wonderful promises—that the convent would not fail to be established; that great service would be done to Him in it; that it should be called Saint Joseph’s; that He would watch over us at one door and Our Lady at the other, that Christ would go with us; that the convent would be a star giving out the most brilliant light. […] for what would become of the world if it were not for religious?”

Nevertheless, similar support was not forthcoming from her superiors, her Carmelite sisters or from Avila society… It was only with great prudence and the support of various men of God—including St. Peter of Alcantara, St. Louis Beltrán, the Bishop of Avila and Fr. Gaspar Daza, among others—that the opposition was surmounted and the necessary reforms brought into effect.

In the city of Avila, with the help from friends, she acquired a small dilapidated house, destined to be the new monastery. Problems arose during renovations: a wall that was being rebuilt fell upon her little nephew; her brother-in-law who was overseeing the work fell ill; the papal bull approving the foundation arrived incomplete from Rome… And when, at the decisive moment, they awoke to find that yet another wall of the house built with the last ducats of Sister Teresa had collapsed, all were tempted to lose heart. She, however, looked at the rubble and said: “If it fell, we must rebuild it.”

Finally, with the necessary approval, on August 24, 1562, the first Mass was celebrated in the Monastery of St. Joseph of Avila, the firstborn among the reformed Carmels. Under the strictest poverty and cloister, Teresa set about forming her sisters, showing them the strength of community life well lived, in obedience and joy. She constantly reminded them of their principal reason for having consecrated their lives: “If we can prevail with God in the smallest degree about this, we shall be fighting His battle even while living a cloistered life and I shall consider as well spent all the trouble to which I have gone in founding this retreat, where I have also tried to ensure that this Rule of Our Lady and Empress shall be kept in its original perfection.”

The great Teresa, yesterday and today

This radical lifestyle attracted many new vocations. When St. Teresa departed for eternity, in 1582, she had founded more than 20 monasteries of the reformed branch, both feminine and masculine. However, as always happens with high callings, the tree she planted continued to grow after her death, providing precious fruits for the Church on the five continents.

After 450 years since the founding of these first monasteries, Pope Benedict XVI considered it fitting to recall the circumstances in which the mystical saint lived, which seem so familiar to us. For the Holy Father, the thought of the holy Carmelite remains relevant, luminous and demands a response from us. “Today too, as in the 16th century and also among rapid changes, trusting prayer must be the soul of the apostolate so that the redemptive message of Jesus Christ rings out with deep clarity and vigorous dynamism. It is urgently necessary that the Word of life be harmoniously vibrant in souls, with resonant and attractive tones. […] Following in the footsteps of Teresa of Jesus, allow me to say to all who have their future before them: may you too, aspire to belong totally to Jesus, only to Jesus and always to Jesus. Do not be afraid to say to Our Lord, as she did, ‘I am yours; I was born for you, what do you want to do with me?’(Poem 2).”

Heeding the divine appeal, St. Teresa knew how to courageously identify the goals of her life with those of God, going down in history as “a great lady, a great woman, a great nun, and a great saint.” For this reason, the introit for the Mass in her honour rightly sings: “The Lord granted her abundant wisdom and prudence, and largeness of heart like the sand on the seashore.”